Pax Pamir Second Edition

Developer: Cole Wehrle

Publisher: Wehrlegig Games

Format: Area Influence, Hand Management, Simulation

Number of Players: 1 - 5

Price: $85

Copy Purchased By Reviewer

Pax Pamir comes to us courtesy of Cole Wehrle, the designer who brought us the wonderful woodland wargame we know as Root. We’ve heaped no small amount of praise on that particularly political conflict, so naturally when I heard a new game was in development boasting political power struggles in 19th century Afghanistan, I was all eyes and ears. A trusted designer plus an underrepresented setting seemed like a winning formula, and I’m happy to report that Pax Pamir sits in that sweet spot of being relatively easy to play while being difficult to play well. Having taught it to several groups at our local game night now, everyone is excited to try their hand at it again. Also it sports absolutely gorgeous production quality.

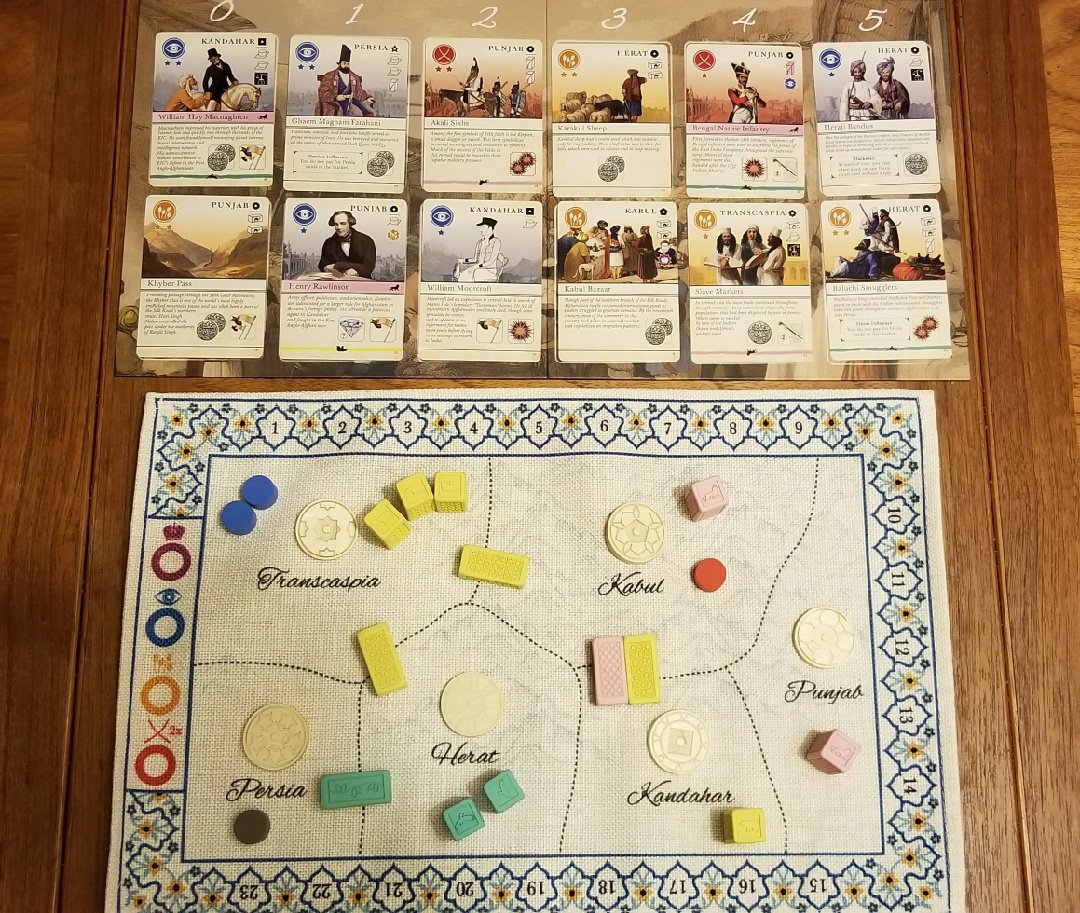

I mean, have a look for yourself!

Resin pieces. Cloth board. This game has so much table presence!

The Great Game

Full disclosure here: I never played the original edition of Pax Pamir. I’ve read up on it though, and the differences are pretty substantial! We’ll get to those in a bit, but first you might be asking, “What is Pax Pamir anyway?” The Great Game, as it was referred to, in more than a cardboard sense my friend; three major powers vying for control after the fall of the Durrani Empire. British, Russian, and Afghan coalitions active in the region with you, a native Afghan tribal leader, playing the foreigners in your land for the most gain in the emergence of a new state.

At its heart, it’s an area influence game where the actions you’re allowed to take are dictated by cards you purchase and play from a central market. You build up a court of historical personalities who control your armies, spies, construction projects, and who act as diplomats to the three dominant powers fighting for control. The actions you can take, such as battle or tax, are limited by the action symbols of the people in your court. How you play against other courts and how you develop your state on the main board are always in flux as power shifts like a ship swaying on the sea.

The three coalition markers: Russian, Afghan, and British. Choose wisely.

Players continue buying cards, playing them to their courts, and taking actions to curry favor with the powers that be until a scoring check is triggered (referred to as a dominance check, of which there are 4 cards seeded into the deck during setup). If one of the factions is considered dominant at that time, that is they have at least four more colored blocks of their coalition on the map than their nearest competitor, that faction scores; only players aligned with the dominant coalition earn points, and players earn more points than their rivals by having more influence within said faction. They do this by killing off certain opposing cards that their faction wants gone, hiring that country’s patriots to their court, and by gifting large sums of money. Should no coalition be considered dominant, players score based on their personal holdings instead, represented by how many markers of your player color you’ve managed to place in play from your supply (though this is ultimately worth less points overall). The game ends when all four dominance cards are resolved or one player has pulled at least 4 points ahead of their second-place opponent. Another easily missed rule is that the final scoring check doubles its rewards, allowing players who are behind to still grasp for a win.

If you think then that this is a dry game about building up an engine within your court, placing colored blocks on a map more efficiently than the other players, and out-scoring them through the power of your economy, you’ve only grasped half this game. You see, nobody said you had to remain loyal to a single coalition! This is less a game about developing the best engine to score as it is making sure you’re standing in just the right spot when the stopwatch clicks.

It’s about deals done, boosting your chosen faction up only to ditch to a rival coalition and mooch points when you realize things aren’t going your way. This is a game about letting someone else do all the heavy lifting before swooping in and stealing their spotlight. This is a game about (true story) watching virtually the whole table jump to Afghans because you’ve been cleaning house with them since the last dominance check only to make a deal with a player near last place, swap to British, and score boatloads of points while you watch the rest of the table go under with a sinking ship. Remember what I said about the in-your-face competition of Tokyo Metro when I reviewed that game? Yeah, turn it up to 11. Things are gonna get mean.

A sample game. Normally the region markers would be claimed if you ruled a region, but they're all featured here for viewing purposes.

A Delicate Balance

That’s not to say everyone’s at each other’s throats for the entire game. You can absolutely make friends with other players. After all, it’s much easier to outpace another faction’s construction (remember you need at least 4 blocks more to be considered dominant) if you have a friend helping you put those pretty pieces down. And just as I praised the mechanics-supported deal making in Root, so too do I see it baked into the game mechanics of Pax Pamir. For example, if I have ruling status in one of the game board’s regions, I can charge players a bribe to play new cards associated with that area, but I can also waive the bribe anytime I want. The things you can do with this one little rule!

This is a brilliant design decision which offers so many wonderful possibilities for play. I can’t refuse the bribe money if I leave the bribe in place, so as long as you manage your economy you can never be completely locked out from an action you really want. Meanwhile, I can waive a bribe for a player who is making a favorable proposition one moment, say boosting up the faction we’re both backing, and later squeeze that same ally for needed cash, even though we’re still working for the same coalition. This can be especially hilarious when you’re both backing the same coalition, as armies of that country won’t attack your tribes on the board (since they won’t attack allied pieces), meaning the other player can’t just retaliate with military force! Also, the game states that you can’t simply give people money as part of deals. It has to be exchanged through in-game mechanisms, so the bribe is one way I can feed players money they need, maybe then enabling them to cause a little trouble for pesky neighbors of mine. Sometimes it pays to get creative.

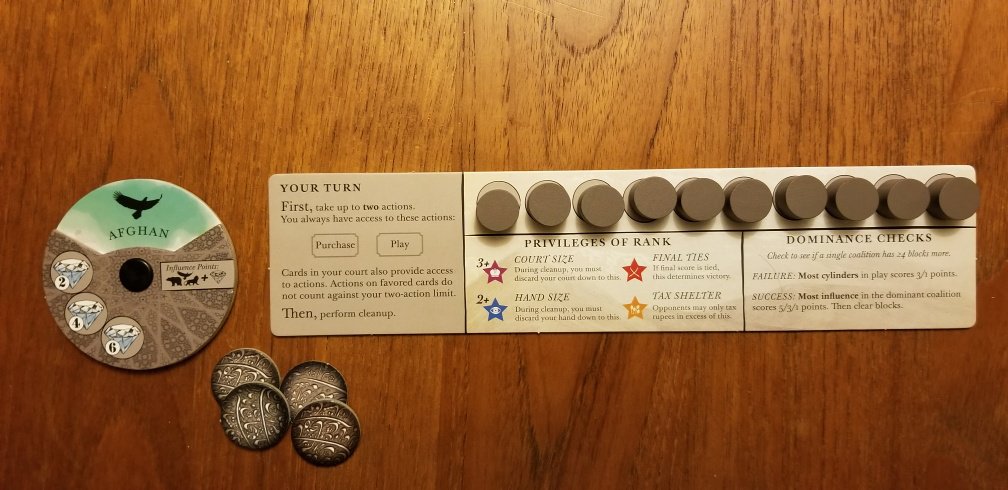

Sample player setup. I love when references are printed on components so I don't have to dig in the rulebook.

Let’s talk a little more about that creativity, because early on it might seem like nothing you need is cycling down the market of cards and everything in your mind’s eye has been reduced to randomness flipped off a deck. Pax Pamir really rewards you for cunning! Even excluding deal making and alliances, it pays to take a step back sometimes and take stock of what you already have. I’ll share a little story from my last game to illustrate my point.

I’m currently backing the Russians alongside another player in a five player game. Battle lines are drawn and two of the other players have teamed up to back the Afghans. Our Russian coalition is currently leading the race to dominance, and things looks like they’ll be an easy score; so I assassinate one of the cards from my own court for additional Russian favor, preparing to take the top spot for influence. Suddenly Afghan construction bursts ahead and both the yellow (us) and green (them) blocks on the board are locked up at six each! I realize that if there’s no dominance, my strong position becomes the weakest; I have the fewest personal tokens in play. My turn is coming around again, so I look down at my options. I have a spy in an opponent’s court, one of my player markers sitting on one of their cards, but I don’t have enough money to pay for another “betray” action (that assassination I’d just done to my own card). I don’t have a person in my court who can “tax” either, so I can’t easily come up with the money to stop that target. But what I do have are movement and attack actions. On my turn, I order Russian armies to march into a neighboring region and destroy Afghan roads. Up until now things have been purely a game of escalation. But when you can’t increase your own holdings, it’s time to decrease theirs! I sit back, the roads that enemy armies would take to counterattack now gone, confident that on my next turn I can attack again to restore dominance for my faction.

Of course, not everything always goes according to plan. You’re not the only cunning one out there after all! That last story ends with the dominance card coming off the deck on the next player’s turn (while randomized, the way the deck is seeded ensures you have a rough idea of when you’re due for one). Paying an exorbitant amount of money to reach all the way up the market, they bought the dominance card, triggering it before I could solidify my position again. A clever move that ultimately lost me the game (and won it for them)! Despite the cutthroat nature of Pax Pamir, sometimes after the dust settles you just have to extend a hand to another player and say, “Well played!”

The art is evocative of the period and I think works well. The second edition makes more room for it on the cards.

Less Is More

You see now how this game follows the adage, “easy to learn, hard to master.” Each turn a player only gets two actions (plus any free actions associated with a card suit tracked on the side of the board), so barring the occasional analysis paralysis turns are very quick. Twice around the board and people understand the basics. Another turn around and they’ve got it down. Five turns around the board and people have spies in other players’ courts, armies meshing on the board, stealing money from each other through taxes. And yet the path to victory is never simple, never obvious. Rules are relatively streamlined while interactions remain complex. Accessible yet crunchy, and always tense, Pax Pamir has all my friends at game night asking to play it again.

I think this owes in no small part to the very clean design I’m seeing out of Cole’s games. Again, as with Root (specifically I’m thinking about how the Riverfolk use army pieces as money), I see a clear intention to minimize the number of different tokens and markers needed to play. Put a colored block standing up on the board, it’s an army; lay it down across a border and it’s a road. Similarly, take a marker off your player board and put it on the map, it’s a tribe. But put it on a card in someone’s court and it becomes a spy. Put one on your coalition allegiance dial and it’s a gift. Everything is easy to track at a sweep of the eyes, and there aren’t so many moving parts to keep track of.

If we come back to the aforementioned differences between the first and second editions of Pax Pamir now, and it may be a bit presumptuous of me to say, I think the elegance of the newer edition is a solid plus. In the first edition, scoring was a complex and convoluted affair that required players to track multiple elements of the game state from move to move. While I can visualize a very satisfying state of intrigue and balance, I’ve heard the mental requirements lead to many slowdowns right around scoring time, grinding the game to a halt. Also, with conditions that jumbled to track, the game was much less accessible to newer players. What we have with the second edition is something that is actually game night friendly while still offering all the tasty decisions, intrigue, military flexing, and broken alliances that you’d expect from Pax Pamir. In terms of the intention of the designer shining through the finished product, I’d say Cole’s hit it out of the park again.

If I had one complaint of the components, it's that three of the player colors are similar shades of stone.

It’s Dangerous To Go Alone

You didn’t think I’d end this review without going over the solo mode included in the game, did you? Truth be told, the Wakhan player is deserving of a mention in its own right, being more than just a simple clock to time your best score against. This AI player operates off a special deck of cards which it draws from once per turn, and while most AI players in other single player games I’ve played operate by their own separate rules, the Wakhan player actually operates very similarly to a real player (it has a couple exceptions, but not many); the card you flip each turn gives instructions on which actions Wakhan will take, and in the case of determining priority (for example, which card it will betray with a spy) it follows a set chart of highest “target value” to lowest. These are printed on reference cards so you don’t have to refer to the rulebook every time you need them. Wakhan is also aligned with all coalitions, so outscoring it can be quite challenging (though its AI cards will tell you which block colors it lays down if it does so).

It’s actually quite refreshing to see! Wakhan will purchase cards from the market. It will grab patriots, and it will pay (if it can afford it) for a dominance card if it stands to score the most points of any player. It moves spies and assassinates other cards! While it can be a bit much to keep track of at first, once you’ve got the hang of how Wakhan acts it’s not very difficult to keep track of it. And while it follows a predictable chart of priorities in terms of purchasing market cards or causing betrayals with spies, its deck of cards adds a nice random element so you’re never quite sure which actions it will prioritize in a given turn. I’m not as big on solo board game play, but this is probably one of the best solo modes I’ve seen. I love that it emulates a real human opponent, and does so quite well.

Keep in mind that if you put Wakhan as a third player to your game with a friend, you can beat on it together all you want but there will still only be one winner in the end. Also, while Wakhan does play like a real player, the fact that it is aligned with all three coalitions at all times means you won’t get the same satisfaction of jumping sides to swing the board state like you can with human players. Personally, I still prefer Pax Pamir when played against human opponents, but I also know that lots of other players love a good solo mode. All in all, I think the addition of the Wakhan player at no additional cost is a brilliant move that only adds to what you get in this box. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend buying Pax Pamir only as a solo game, but I’m very glad the solo mode was included with it.

A removable tray for the faction pieces is a small, but welcome, detail.

A New Leader Emerges

What you get in this box is, frankly, worth its literal price of entry; it goes for $85 directly from Wehrlegig Games (US shipping only via this seller), but you have to consider the production quality you’re getting. It’s got resin pieces, a cloth mat board, thick cardboard dials, a sturdy box, and an insert that cleanly holds everything. The tray the resin pieces rest in is also removable, which is a classy touch. As a physical thing that’s just really nice to move in one’s hands and behold on the table, this board game really fires on all cylinders. I think the price is fair considering what you get, but whether it’s worth that cost to you is something you will need to evaluate individually.

So who else isn’t this game for? Well, to put it bluntly, my family. What I mean by that is, my family isn’t the type to gravitate towards directly confrontational games. With the exception of Cosmic Encounter (which I will probably never fully understand), my family doesn’t enjoy games that are in-your-face. Those from my immediate family love party games and light strategy, while my in-laws prefer engine building games and action selection or worker placement. Does this sound like your group at all, because this is the kind of game that needs you to be ready to lose parts of your engine from time to time. While you could play Pax Pamir as “3 players,” two humans teaming up against the solo mode AI, buying this game only to play like that seems like going to a fancy restaurant for a 3 course meal and only eating the dessert. Ultimately it’s your money and your decision on how you like to play, but you’re missing out on a lot if you don’t experience that ebb and flow that a 4 or 5 player game provides.

Finally, by the way, if you’re already an owner of the original Pax Pamir but still like the look of the second edition, the two are distinct enough that I think you could happily keep both on your shelves. Having one doesn’t necessarily discount the other from consideration.

Comparison of stock coins to optional metal ones (not included in the base game). Keep an eye for another print run of the metal coins.

I wanted to end this review by just saying what a thoughtful game this truly is. It takes the perspective of Afghan natives using the foreigners in their lands for their own gain, a nice take on what could clearly have been an insensitive colonial theme. And as evident by some of Cole’s designer diaries, addressing the troublesome idea that history viewed in hindsight isn’t full of grand, deterministic events, but rather a set of very fluid, sometimes shaky outcomes that came together into what we see today, is a fun sandbox to play in. It turns the view of history I learned in school on its head, and I like it. Forgive me for making the comparison one more time, but if Root was criticized by some as strictly a wargame with no regard for its political implications and aspects, I think Pax Pamir makes that power dynamic playground very much more apparent. And the second edition makes this game more accessible and easy to get into than ever. Not to mention, the card art is evocative and the flavor text on each card ensures that you can learn a little about anyone in the game if you’d like. If you want more than that, the last page of the rulebook even gives a list of recommended readings that influenced research on the game.

A game like this doesn’t come along very often, so for me this game is a must-purchase. But again, that’s for me. Ultimately, what good is a game as a collectible over being, you know, actually played? If this sounds like a game for you, if you have a group that enjoys ever-changing board states and cunningly adapting on the fly, and if the price point isn’t above your spending limit, I strongly urge you to try it. This definitely isn’t a game for everyone, but what game is? For others, this will have you scratching your head, muttering under your breath, laughing out loud, and asking for just one more chance at glory. You know which coalition you fall in to.